Dorothy Grebenak

As published in Hyperallergic on April 5, 2017

This essay for Hyperallergic arose from a chance encounter with Dorothy Grebenak’s work in Allan Stone Projects, which primarily presents works from the gallery’s enormous archive. One advantage of approaching postwar art from a craft lens is that it affords opportunities to recover artists like Grebenak, whose gender was bound to marginalize her in the 1960s. The same impulse lay behind the exhibition Pathmakers: Women in Art, Craft and Design, Midcentury and Today, curated by Ezra Shales and Jennifer Scanlan, during my period of directorship at the Museum of Arts and Design.

Dorothy Grebenak, “NRA Tapestry (National Recovery Administration)” (1963), wool, 54 x 41 in. (all images courtesy Allan Stone Gallery and the artist’s estate)

Here are a few things we know about Dorothy Grebenak. She is now remembered — to the extent she is remembered at all — as one of a handful of female Pop artists. Yet she once said, “I don’t think what I do is Pop Art.” Her work was acquired by an impressive list of New York collectors, including the Rockefellers, and she was represented by leading dealer Allan Stone. Yet even her supporters put her works on the floor and walked all over them. Stone discovered her works in the Brooklyn Museum of Art — but not in the galleries. They were on sale in the gift shop.

A few other points of information: she was married to painter Louis Grebenak, who started out as a WPA muralist and became a hard-edge abstractionist. She began working in the 1950s, living on Montgomery Avenue in Park Slope, Brooklyn, and stopped in 1970, when she moved to Europe. She was born in 1913, and died in 1990.

And that’s about all we know. Except for one last thing: she worked almost exclusively in the medium of hooked rugs.

In the annals of overlooked artists, Grebenak is an extreme case. Working in an era when art world acceptance was hard to come by for women even in the best of circumstances, she doubled her marginality by choosing a medium that was relegated firmly to the “minor” arts. In the end, her work would be almost entirely erased from art history, even though she was already making works based on everyday graphics in 1963, only one year after Andy Warhol’s Soup Cans. A selection of her work from the 1960s is now on view at Allan Stone Projects, which continually reaches into its archive to unearth such unfamiliar discoveries. A reconsideration seems timely, even if the paucity of information is frustrating. What can we say about Grebenak on the evidence of the work itself?

Dorothy Grebenak, circa 1964

One of her earliest appropriations depicts a poster for the NRA (the National Recovery Administration, not the gun lobby) reading “Consumer U.S. – We Do Our Part.” This work, and several others, riff cleverly on Warhol’s own sardonic engagement with commodity status. As if in rejoinder to his screenprinted depictions of currency, she made “Two-Dollar Bill” (1964). He made Brillo Boxes; she depicted a Tide detergent bottle. He portrayed Elvis in the western flick Flaming Star; she riffed on Audrey Hepburn’s My Fair Lady. She did a baseball card (Babe Ruth), and he did one too (Pete Rose) — though in that case, his was quite a few years later.

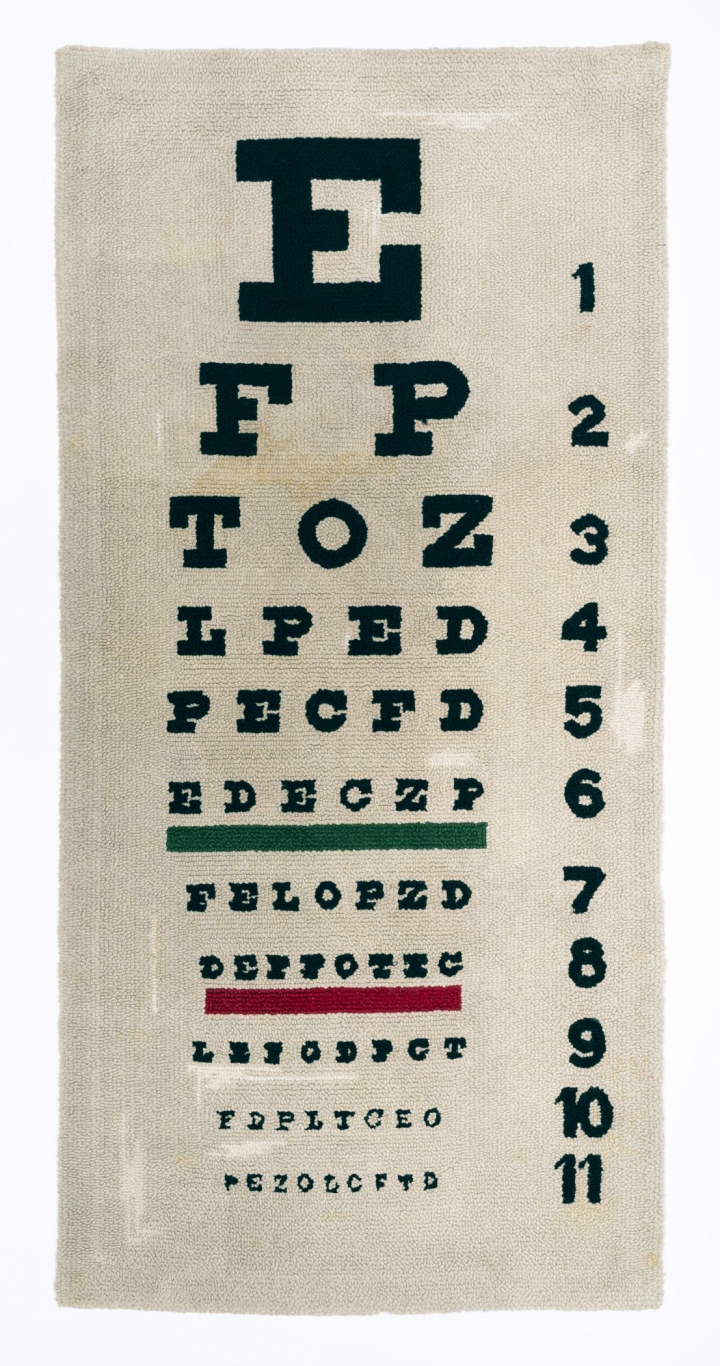

Dorothy Grebenak, “Eye Chart” (1964), wool, 32 ½ x 68 in.

The art historian Michael Lobel also discovered an instance in which Grebenak crafted a rejoinder to Roy Lichtenstein, specifically a work depicting a man peering through a round porthole into a dark space: “I can see the whole room — and there’s nobody in it.” As was often his practice, Lichtenstein stripped down the source image, from the comic strip Steve Roper, rewriting the text slightly and removing the original artists’ signatures. In 1963, both the work and the source were reproduced in an article in Art News entitled “Pop Artists Or Copy Cats?,” written by an aggrieved illustrator whose work had also been appropriated by Lichtenstein. Grebenak was evidently attracted by this incident, for in 1964 she showed a rug work which reproduced the image again — not in Lichtenstein’s version, but just as it had appeared in Steve Roper, complete with the original signatures. It is difficult to read her intentions, but certainly it is possible that she wanted to indicate sympathy with the commercial artists whose work had been quoted; her show at Allan Stone (which she shared with the artist John Fischer) was pointedly entitled Odd Man In. It is also intriguing that the image — in all three versions — takes the act of looking as its central theme. This was a persistent concern of Lichtenstein’s, and evidently also of Grebenak’s, as we can conclude from another 1964 work, “Eye Chart.” Though Allan Stone kept the rug work on the floor — it has numerous repairs today — it is best seen on a wall, hung at optician-office height, an object that explicitly acknowledges your own gaze.

Odd Man In, installation at Allan Stone Gallery, 1964

So Grebenak was in dialogue with her peers in Pop, but the conversation went only one way. That’s because, along with the fact that she happened to be a woman, her medium invalidated her from the outset — it was why she landed in the Brooklyn Museum’s gift shop. On the other hand, it offered a route into collectors’ homes. When Albert and Vera List bought Grebenak’s work “Tide,” they placed it on their kitchen floor. In 2010, when the organizers of an exhibition about women in Pop Art went looking for it, they discovered that it had been destroyed by years of wear (they had it remade, a curatorial maneuver which likely would not have been done for a painting). This is a sad tale, and a reminder of the fact that Grebenak’s limited art world success came only because she made objects that could pass as décor. In the midcentury, marginal art forms, like ceramics, weaving, and photography, were the onlygenres in which women could establish themselves professionally. Grebenak’s rugs slipped right under the art world’s attention, but at least she got through the front door.

Dorothy Grebenak making a rubbing of a manhole cover, circa 1964

Dorothy Grebenak, “Con Edison Co.” (1963), wool, 31 1/2 x 31 1/2 in.

Grebenak’s iconography was similarly unassuming — classic deadpan Pop — but was unusual in that it was drawn from public spaces. She reworked New York’s streets with her needle punch, both literally and figuratively. Her most common motifs were manhole covers, based on charcoal rubbings, a series she had begun by 1963. Grebenak also had a keen eye for signage. “Four Roses,” circa 1964, has nothing to do with the whisky brand of that name; it seems to have been grabbed from a florist’s sidewalk display. The serial, flip-flopping lettering comes across as concrete poetry, and juxtaposed with the floral motif, prompts thoughts of Gertrude Stein.

Dorothy Grebenak, “Four Roses” (1964), wool, 26 x 90 in.

Another work, perhaps thought up in the back of a cab, depicts a taxi driver’s badge. It reads “Licensed Public Hack” — not a bad self-description for an aspiring Pop Artist. In another, a monumental payphone dial communicates a sense of panic, the numbers 440-1234 at its center being the city emergency line — the 1960s version of 911. And then there is a startling work that simply reads OBSCENE, in huge block letters. The word collides head-on with the stereotype of hooked rugs as a decorous medium — a contradiction that speaks with powerful concision to the changing cultural norms of the 1960s.

Dorothy Grebenak, “Licensed Public Hack” (circa 1960s), wool, 30 x 28 1/2 in.

Dorothy Grebenak, “440-1234” (1960s), wool, 41 x 41 in. (Private collection, Europe)

Dorothy Grebenak, “Obscene” (1960s), wool, 26 x 71 in. (Collection of Jessie Stone)

Grebenak also made rugs with abstract meander designs, simple mazes of block colors. These initially puzzled me — and perhaps the folks at Allan Stone Projects too, as they were not included in the current exhibition — because they seem so disconnected from the found iconography seen elsewhere in her work. Were the mazes meant to acknowledge quilts and other historical textiles? Do they betray an affinity for hard-edge abstraction by the likes of Frank Stella (or her own husband, for that matter)? Or should we simply interpret them as emblematizing her identity as a watchful wanderer, a latter-day flâneur of the city streets?

Dorothy Grebenak, “Yellow, Red, Blue” (1964), wool, 36 x 32 in.

Of course, Grebenak may well have had other ideas entirely. A single, solitary quotation about her art comes down to us, from a brief 1965 article in the New York Times which surveyed the work of several Pop artists. As it happens, it is not particularly helpful in making a strong case for the seriousness of her art. “I don’t think what I do is Pop Art,” she said. “People who name things probably would, but I don’t like labels. I think transposing something from one medium to another is droll. The idea of a big $5 bill makes me laugh.” Maybe that’s all there was to her work: just a little joke, nothing for mainstream art history to concern itself with. Imagine, however, that we only had one offhand comment, plucked at random by a journalist, to document everything there was to know about Warhol, or Lichtenstein. Then look again at Grebenak’s works, and just think what we might be missing.

Perhaps it’s best to not take Grebenak at her word. Yes, she was definitely a Pop artist, and an early and acute contributor to the movement at that. Transposing something from one medium to another is a lot more than “droll” — it is one of the key strategies of the avant-garde. And if her art makes us laugh — as indeed it might, given the gimlet eye she turned to the world — well, that’s fine. Just one more reason to value her work. Better late than never.

Two Views Of Pop: Don Nice And Dorothy Grebenak continues at Allan Stone Projects (535 W 22nd Street, 3rd Floor, Chelsea, Manhattan) through April 22.