Woman Up: Nina Yankowitz Defies the Patriarchy

Published in Art in America, January 12, 2023

View of Nina Yankowitz's exhibition "Can Women Have One-Man Shows?," at Eric Firestone Gallery,New York, 2022.

PHOTO JENNY GORMAN/COURTESY ERIC FIRESTONE GALLERY, NEW YORK

In 1972, the year that art historian Cindy Nemser cofounded the Feminist Art Journal, she fired off a letter to the New York Times, taking critic James Mellow to task for labeling a female artist’s exhibition a “one-man show.” “Evidently,” she wrote, “Mellow still has not caught on to the fact that women are not ashamed of their sex and resent being mistaken for men.” After protesting the reviewer’s chauvinistic language—the work was “seductive,” “feminine,” even “en déshabillé”—Nemser closed with a scorcher: “Sexist critics take note. When you start seeing scantily clad females in every abstract painting, they may start calling you ‘a dirty old man.’”

The artist in question was Nina Yankowitz, and the show was her second solo at Kornblee Gallery in New York. This past autumn, some of the same paintings were back on public view in “Can Women Have One-Man Shows?” at Eric Firestone’s two-floor space on Great Jones Street. By alluding to Nemser’s letter so directly, the exhibition not only positioned Yankowitz as a significant figure in feminist art, but also raised the issue of her early work’s reception—or lack thereof.

Made between 1967 and 1972, these breakthrough paintings were sprayed in gorgeous veils of acrylic, here and there disrupted by vigorous splashes, and in some cases relieved by stark geometric figures, created by masking the raw canvas. The unstretched paintings, averaging roughly 10 by 5 feet, were then variously draped, pleated, and hung on the wall, where they looked—as if by some sleight of hand—positively monumental.

The Firestone show included 15 of these signature works, all of them lent by the artist herself. We’ve become accustomed of late to women practitioners and artists of color being belatedly retrieved from obscurity. But Yankowitz’s case is extreme. In just one glance, you can see that these draped paintings match the caliber of contemporaneous works by Sam Gilliam and Lynda Benglis. Learn a bit more, and you realize that they are powerful icons of feminist art, made when Yankowitz was bridging Post-Minimalism and the subsequent Pattern and Decoration movement. These paintings ought to be in the collections of the Whitney Museum, the Museum of Modern Art, and other major institutions. Instead, they have been in storage for 50 years. How did this happen?

Nina Yankowitz, Draped Drips, 1970. acrylic spray with compressor on canvas

Gender has a lot to do with it. In a recent Archives of American Art interview, Yankowitz commented, “no matter what strides women were making as I entered into my art practice, you were lucky to be considered, but it was very rare…. Exposure was limited and choppy, to say the least.” Keenly alive to this reality, she became a founding member of Heresies, the most significant feminist art collective on the East Coast. But there were also other factors at play. First of all, she’d started young. Yankowitz was just 21 when she made the first of the draped works, as a student at the School of Visual Arts in New York, where she earned her undergraduate degree in 1969.

Second, far from being a self-promoting sort, Yankowitz was an outlier, attracted to the radical fringes of the counterculture. That journey began when she was growing up in New Jersey; she’d hop a bus to Manhattan and get herself to Greenwich Village. By 1968 she was spending time upstate in Woodstock, hanging her new paintings from trees and sometimes performing with experimental musicians associated with Group 212.

In collaboration with Phil Harmonic (born Ken Werner), she developed audio for the painting Oh Say Can You See (1968). This work, bearing a musical staff with the first few notes of the “Star-Spangled Banner,” was accompanied by a sound piece that Harmonic made by manipulating the melody on an early Moog synthesizer. It was a cross-disciplinary experiment, the notes filling the canvas while being electronically stretched in the audio component. At the same time, it was an insouciant metaphor for America’s unstable, shifting identity, anticipating Jimi Hendrix’s famous distortion-filled rendition of the national anthem at the Woodstock festival the following year.

There are touches of political satire in the draped paintings too: one work is called Sagging Spiro (1969), a mocking allusion to Richard Nixon’s notoriously conservative (and jowly) vice president. But primarily, Yankowitz was working in diametric opposition to Hard-Edge Abstraction, then at the height of its currency. Her idea was to “emasculate” this genre, answering it with an alternative soft power, conjuring the body in motion. In 1968–69, she created a series of set designs for choreographer Pearl Lang, a disciple of Martha Graham. Yankowitz developed shapes in folded cardboard and then had them fabricated in sheet steel, giving them (along with duct-like metal tubes) to the dancers to interact with. In a related experiment, in 1969, she dropped a canvas from a 10-foot ledge, using a stop-motion camera to capture the shapes it assumed as it fell. The best moment, she thought, was when it first crumpled against the ground.

Yankowitz was one of many artists exploring gravitational effects at the time, among them Sam Gilliam (whose draped paintings Yankowitz had not seen prior to developing her own), Robert Morris (whose felt works she admired), and Eva Hesse (whose arrangements of string and cloth she knew through their mutual friend, Sol LeWitt). All investigated how a composition could seemingly make itself when dropped into space—a formal link that was recognized at the time. Yankowitz and Hesse were the only women included in the 12-person survey “Hanging/Leaning,” at the Emily Lowe Gallery at Hofstra University in 1970. Robert Pincus-Witten, in an Artforum review of Yankowitz’s 1971 Kornblee show, compared her directly to Gilliam, who was having a concurrent exhibition at MoMA. Like Mellow, Pincus-Witten used patronizingly patriarchal language: “the essential loveliness of the work is beyond contest, although the devices of her art seem to be outmoded.… [H]er lack of aggressiveness indicates that she remains on a sill which, once crossed, will bring her beyond mere stylistic hold.”

There’s a lot to disagree with there, but Pincus-Witten was right to compare Yankowitz to Gilliam. Both were after an expressive coloristic sublimity, an effect that Yankowitz described to me as we walked through her Firestone show, as a “gestalt.” She used this term neither in the psychological sense nor as an allusion to Morris’s Notes on Sculpture, she explained, but rather to describe her immersive aesthetic: “it’s like everything I do. There’s no beginning, no end. You’re just in it, the whole surround.”

Another reason Yankowitz’s draped paintings have not become canonical—yet—is that she was too creatively restless to consolidate her achievement. Moving quickly through ideas, she first incorporated new features to her draped paintings that enhanced their affinity to structured garments, adding narrow pleats by running the canvases through a machine press, and subsequently introducing stitched lines, which cause the fabric to alternately pucker in and balloon out. (The stitching was done for her by professional sailmakers. “I don’t know how to sew,” she said wryly. “Let’s put that way.”) One work, Opened Flat (1971), has webbing straps crossing it horizontally, as if pinioning it to the wall. This makes explicit Yankowitz’s idea of “flattening an enclosure”—an inversion of the dynamics of representational painting, in which a flat surface is used to evoke 3D space.

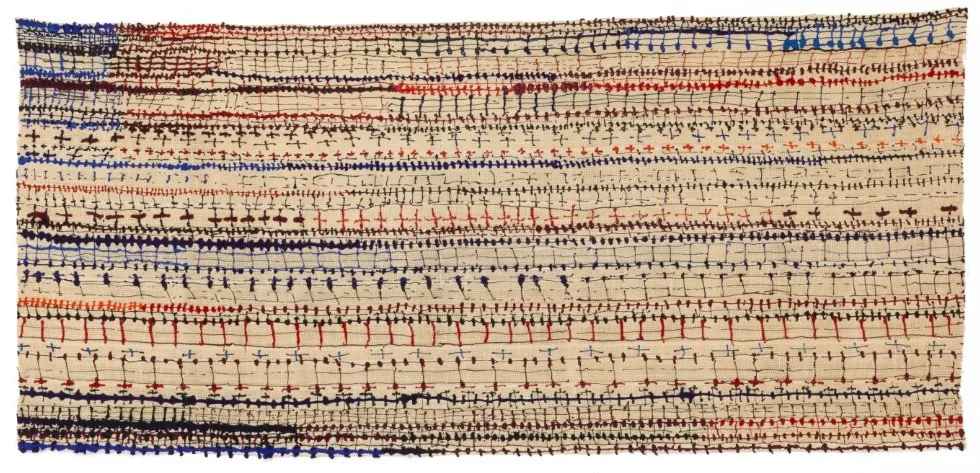

Dilated Grain Reading: Scanning Reds and Blues, 1973, extruded acrylic and flash paint on linen, 50 by 109 inches.

PHOTO JENNY GORMAN/COURTESY ERIC FIRESTONE GALLERY

With these initial moves, Yankowitz broadened the effect of her draped paintings without abandoning their essential features. But then, in 1972, she made a dramatic change. The downstairs space at Firestone displayed several examples from her next series, “Dilated Grain Readings.” Though also unstretched, these paintings are cool instead of lush, system-based rather than gestural. Yankowitz had the linen canvases custom made in a very open weave, almost like netting.

To this richly textured ground she added regular marks that suggest a musical score or pulsing sound waves. (The paints she mixed herself, in a combination of acrylic and Flashe paint, to get the color adjacencies and viscosity she wanted.) Finally, picking up where she’d left off with Oh Say Can You See, she paired the paintings with a soundscape, this time creating it herself from field recordings she made in Little Italy and Chinatown. “When I hear sound, I see color; and when I see color, I hear sounds,” she has said, and these works do effectively conjure that synesthetic experience.

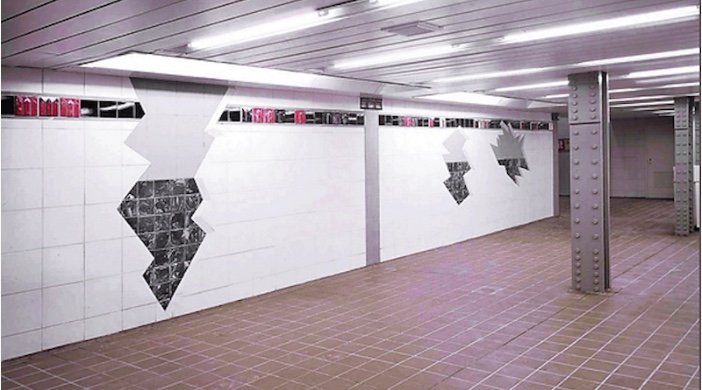

View of Tunnel Vision, 1989, tile wall installation at the the Lexington Avenue and 51st Street subway station, New York.COURTESY THE ARTIST AND COMPANY AGENDA

For the last five decades, Yankowitz has continued to explore the fusion of music, technology, and visual art. She mastered the vocoder, the voice distortion device. She explored the possibilities of ceramic tile—notably in Tunnel Vision (1989), an illusory “wall damage” installation at the Lexington Avenue and 51st Street subway station—and showed avant-garde furniture at the legendary design gallery Art et Industrie. She made sensitive, surrealistic drawings on vellum. Since the late 1980s she has been exploring interactive gaming and, more recently, social media. There are definitely through lines in all this work, above all, an interest in activating a relationship with the viewer’s body. But Yankowitz’s oeuvre is also impressively, even confoundingly diverse—and by no means a linear development from her early paintings.

Given the value we place on variety and inventiveness, Yankowitz’s refusal to tidily arrange her career might well make her a positive role model. That said, however, it is high time for her early draped paintings to be recognized as a precocious achievement. In a statement for the Brooklyn Museum’s feminist art center, Yankowitz has called for the “righting of history” and an end to “important contributions disappearing … into the trash—Poof.”

So can women have “one-man” shows, as solo offerings were reflexively designated in the ’70s? The answer ought to be more than clear by now. No they can’t, but they can damn well be accorded the art historical stature they deserve.